Just before noon on that Monday, April 16, 1984, we stood in the newsroom’s Metro area, awaiting the Pulitzer announcements from Columbia. At 12:03 p.m., both the Associated Press and United Press International teletypes churned out the news. The UPI bulletin said:

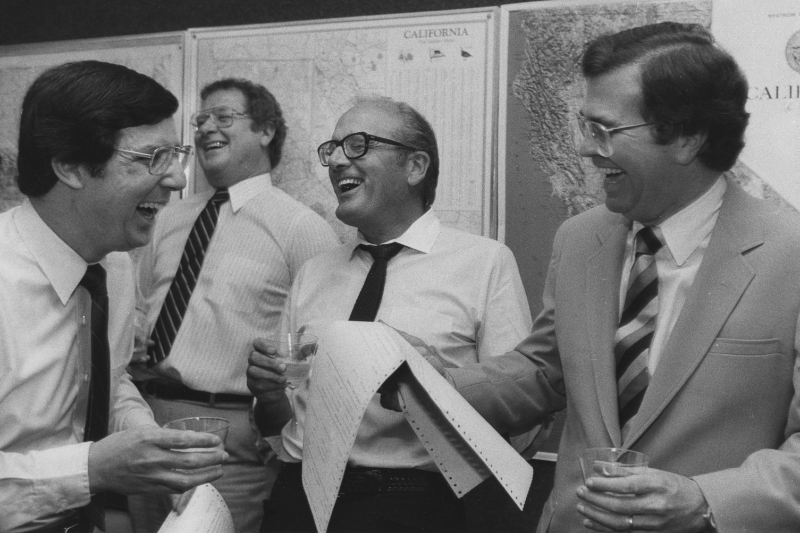

Champagne corks popped and the celebration began. Publisher Tom Johnson and Managing Editor George Cotliar congratulated the team. Thomas was still on vacation. Paul Conrad joined us and celebrated winning his third Pulitzer in editorial cartooning. As the bubbly was poured and cameras clicked, team members hugged and smiled—big, wide smiles.

Noel Greenwood saluted our team, saying: “A lot of people put their body and soul into this project.”

Ramos later remembered that afternoon as was “one of the few times I was actually speechless. All the stuff that we had gone through, the doubt on the part of some colleagues, it just kinda melted away and then you said, ‘Well, it was worth it.’ ”

Soon we were taking calls from reporters and well-wishers. An especially gratifying message came from Abe Rosenthal, the esteemed editor of the New York Times. Publisher Johnson said he received calls and letters from publishers and editors across the country, including Don Graham and Ben Bradlee of the Washington Post, Lou Boccardi of AP and Arthur Ochs Sulzberger of the New York Times.

After the Pulitzer announcement, we received a mailgram from Guillermo Martinez, an NAHJ founder from the Miami Herald, who said: “East Coast Latinos overjoyed at L.A. Times Pulitzer.

That sentiment echoed what we had sensed at NAHJ. “I recall everyone at NAHJ being happy for us,” Julio Moran said. “Our Latino colleagues really felt a sense of pride with us. They shared in our victory because it really was a reflection on all Latino journalists at the time.”

On the Times front page the next day, reporter David Shaw wrote: “In 10 of the 12 journalism categories this year, including both of those won by The Times, the Pulitzer Prize Board exercised its right to disagree with its nominating juries and awarded Pulitzers to nominees other than the juries’ first choices.

Maynard told Shaw that all three nominees in Public Service were “equally worthy of being recognized.” He called the board’s decision to give the gold medal to The Times for its Latino series “terrific.… That series was a splendid piece of work … absolutely outstanding.”

Off to New York, N.Y.

The ceremony in New York to hand out the Pulitzers was approaching, and Greenwood informed Ramos and me that only eight team members, including us, could attend. Choosing who would go was one of the toughest decisions we made. Understandably, it made for some hurt feelings. Ramos and I chose Frank Del Olmo, Robert Montemayor, Virginia Escalante, José Galvez, Louis Sahagun and David Reyes.

The Times told us we’d fly first class and we’d stay a couple of nights at, get this, the swanky Plaza. We made a counteroffer: We’ll fly economy but put us up for more nights at the hotel. The bosses, still jubilant, agreed. When a group of us arrived at Kennedy Airport, a Times-arranged limo shuttled us to The Plaza.

The ceremony to honor the Pulitzers winners in U.S. journalism and the arts took place May 21 at the Rotunda of Columbia University’s Low Library. It was the first year that such an awards luncheon had been held. We shook hands with Walter Cronkite and other media luminaries. This was the year that a special Pulitzer citation was awarded to “Dr. Seuss” for his beloved children’s books. But I don’t recall if Theodor Seuss Geisel or a cat in a hat was there.

I felt humble and proud at the same time when Michael I. Sovern, Columbia’s president, began the ceremony by naming some former Pulitzer winners. Those winners had included journalists Ernie Pyle and Walter Lippmann, and from the world of literature, William Faulkner, Ernest Hemingway, John Steinbeck, Pearl Buck and John F. Kennedy. Sovern said such Pulitzer winners over the years had “changed our way of seeing ourselves and our world.”

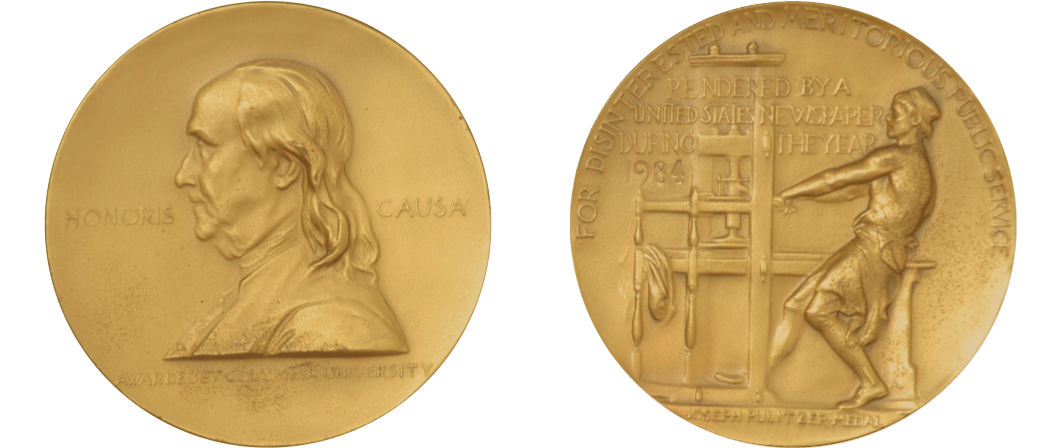

The Pulitzer Gold Medal

He also noted that Joseph Pulitzer, in providing for the awards, had expressed the hope that the prizes would encourage “public service, public morals, American literature and the advancement of education.”

Then it was time for the award presentations. I had seen a letter from Columbia a week before saying that “to keep the ceremony to a reasonable length,” no acceptance speeches would be allowed. Sovern concluded his remarks and said: “And now I invite to the podium, to accept the Pulitzer Prize for Public Service, on behalf of the Los Angeles Times and its exceptionally talented … team of Mexican American reporters and editors … William Thomas.” Thomas accepted the gold medal, emblematic of the Public Service award, on behalf of the Los Angeles Times. I was seated far back in the room and don’t remember even seeing Thomas as he accepted. He said “thank you” and went back to his seat alongside Noel Greenwood.

Virginia Escalante, seated at another table, had paid for her father and a younger brother to fly from Arizona to join her for the ceremony. “I just wanted someone from my family to be there because they were part of my story, and my father was so proud,” Escalante said. Although we had been told that seating would be limited, Escalante’s dad and brother were welcomed at the event.

But Escalante and a couple of colleagues, including Robert Montemayor, were outraged that Thomas, in accepting the award, had not looked back at our team and had not given us a nod or wave of recognition.

“A slap in the face”

“He did not even acknowledge that we were in the room … that we were the ones who had worked and produced that series. Nothing,” Escalante said. “It was a slap in the face.”

(I would have liked to have asked Thomas whether he was aware that some of our team members felt he had disrespected them; however, he died in 2014, long before I started this story.)

Later, a group of us headed to the Blue Note in Greenwich Village to listen to Latin jazz and to celebrate our victory. We returned to the Plaza but weren’t quite ready to end the celebration. Sahagun’s room was close so we went there. Del Olmo, Montemayor, Galvez, Sahagun, Reyes and I joked and drank into the wee hours and we went a wee bit overboard in our celebration. After ordering some food and an early round of drinks, Ramos dialed room service.

In his booming command voice, Ramos said: “This is room so and so. Bring us two bottles of one of your best champagnes.” And when that was gone, he ordered two more. Finally, we headed to our rooms.

“Drinks with peers”

As we were checking out and Sahagun got the bill, he got rattled. How will I report this huge bill on my expense report, he asked? Someone told him, just say: “Drinks with peers.”

It wasn’t all “cheers!” once Sahagun returned to L.A. As he recalled: “Dennis Britton, a deputy managing editor, ordered me to report to his office—pronto. When I got there, he said, ‘Sahagun, close the door and sit down.’ Then, shaking, ‘I’m looking at your hotel bill and, dammit, it shows that $80 bottles of champagne were delivered to your room at 1 a.m. and again at 3 a.m. What the hell is going on here?’ ”

“I sheepishly explained the situation—and the revelry that prompted it.”

“He said, ‘I’m going to let it go, but DON’T. EVER. LET. THIS. HAPPEN. AGAIN! Do you understand me, Louis?’ ”

“I said, ‘I do and it won’t.’ That was the end of the matter. Dennis and I had a great working relationship ever after.”

Dinners and plaques

Once we got back to L.A., the receptions and honors for our team kept on coming. Publisher Johnson threw a dinner for us at Chasen’s restaurant. In a recent email, he said: “What I recall most was the tremendous sense of pride that I felt when the Pulitzer Prize was awarded to the Times for the Latino series. I felt special pride for the team of reporters and editors who had devoted such comprehensive research and effort to the project.”

Johnson sent me a host of congratulatory letters from his files. One, a surprise, had come from LAPD Chief Daryl Gates, an obstinate, hard-headed law-and-order advocate who was repeatedly criticized for his dealings with minority communities. He lauded the series, which he said was being read by cadets training at the Police Academy.

A week after the Pulitzer announcement, Thomas sent a congratulatory letter to team members and provided this same quote for the Times’ in-house publication. In part, it said:

“The series was unique in concept and execution, and it reflected a rare commitment to thoroughness and quality on the part of everyone involved. This truly was exceptional journalism. It certainly deserved the prize …”

He did not note, of course, that he had once opposed the series’ nomination.

Thomas and Johnson agreed to have plaques made for each team member. The foundry where the gold medal had been cast agreed to make copies mounted on handsome wood frames.

Greenwood’s central role

The Pulitzer enhanced Greenwood’s stature. He had become deputy managing editor in 1983. Later, he was a top candidate to succeed Thomas but was passed over in favor of Shelby Coffey III. I believe Greenwood’s role in the Latino series was one of his best achievements and, when he died in 2013 at age 75, I was disappointed that his central role in the Latino series was not acknowledged in his L.A. Times obit.

Terry Schwadron, who had worked closely with Greenwood as executive news editor for Metro, provided this assessment in an email: “Noel’s frustrations with hypocrisy and racism in society were evident to anyone who worked with him. He was delighted with the idea behind the Latino project and served as its proudest supporter. His enthusiasm made the issues of selling top management on providing resources and space in the newspaper easy.”

Late in 1984, the Associated Press Managing Editors Association selected our series as winner of its Public Service Award, citing its effort to “promote community awareness and understanding. The California/Nevada region of United Press International also honored the series.

In an especially meaningful event, our friends from the California Chicano News Media Association honored our team, and we all took to the dance floor at the Beverly Wilshire in celebration. In addition, La Opinión newspaper treated us to a party at the Newport Beach home of Publisher Ignacio E. Lozano Jr.

“Suddenly, everybody was taking notice of you,” Ramos recalled. “It’s like winning an Oscar. Every Latino organization, be they engineers, be they teachers, be they police officers, be they probation officers, be they bankers, suddenly wanted to recognize us as role models. We were the first Mexican Americans ever to win a Pulitzer Prize. That's a big deal.”