On January 4, 1983, the team reported for work, ready to take on our assignment of a lifetime. Along with energy and enthusiasm, a few of us felt a bit of apprehension. Here we were, ready to take on what was surely one of the biggest reporting projects in the 101-year history of the L.A. Times. Even the self-assured Ramos, an Army artillery captain during the Vietnam War, later admitted experiencing some anxiety.

Louis Sahagun recalled: “It was a privilege—and scary as hell—to be part of the effort. That’s because it was overshadowed by the skepticism of many Anglos in the newsroom who dismissed it as ‘a lightweight’ journalistic exercise in political correctness.”

One fellow reporter chortled when he asked Julio Moran: “You guys going to write your stories in spray paint?”

Reverse discrimination?

Along with “political correctness,” the term “reverse discrimination” had gained currency. In 1974, Allan Paul Bakke sued the University of California, alleging that he had been denied admission to a UC medical school because affirmative action programs had set aside spaces for racial minorities. In 1978, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld affirmative action programs but ruled against setting quotas. During the 1970s, the term “reverse discrimination” was flung about by some white men who alleged they were being thrown to the sidelines in favor of women and racial minorities.

“I think all Latinos across the country in mainstream media were being questioned—are they simply affirmative action hires or can they do the work,” reporter Julio Moran recalled.

Reporter Marita Hernandez never forgot the stinging incident she experienced not long after being hired at the San Jose Mercury News. When she went to the metro editor’s office to lobby for a better assignment, he denied her request, adding: “We both know why you’re here.”

Colleagues’ support and sarcasm

All eyes seemed to focus on our team as we gathered in a converted conference room with floor-to-ceiling glass. Colleagues walked by and cast long stares as we worked. Most were curious but supportive. A few others tossed snide comments our way. We were confident in our plans and in our talents, but we did not know what lay ahead. We were about to climb aboard a roller coaster of emotions filled with disappointments and triumphs, but we were raring to go.

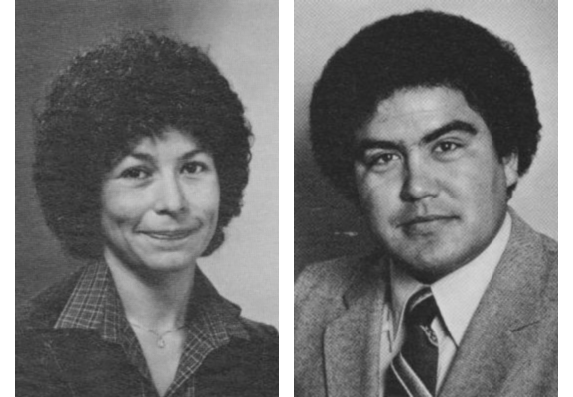

Ramos and I split up the 11 reporters; each of us would keep close tabs on half, help them to shape their stories and follow through on detailed editing. Noel Greenwood would have an important hand in the final content edit of each story.

Our staff had a good mix of experienced reporters—Frank del Olmo, Marita Hernandez, Robert Montemayor, David Reyes and Juan Vasquez—plus five less-experienced reporters who had been at the Times for less than two years: Virginia Escalante, Julio Moran, Nancy Rivera, Louis Sahagun and Victor Valle. The lead photographer was José Galvez, assisted by photo staffer Rick Corrales, plus José Aurelio Barrera, a photo intern, and Monica Almeida, a news assistant in the Southeast section. Ramos and I did double duty, editing and writing for the series.

Korean War veteran

We scored a coup when Al Martinez, one of the paper's finest writers, joined our team. He had been hesitant about working with us. He was older (he was 55; our average age was 35). He felt uncomfortable with us because he did not speak Spanish although he needn’t have worried: Our meetings were in English with just an occasional word or phrase in Spanish. Martinez had been raised in Oakland, and his stepfather had forbidden him to speak Spanish. After serving in the Korean War, Martinez honed his writing chops at the Oakland Tribune.

Of the 17 team members, all but Martinez had studied journalism or photojournalism in college, most of us at state universities in California, Arizona or Texas. Most came from blue-collar households. Ten team members had grown up in the Los Angeles area.

Our team tackled an ambitious list of stories, including such topics as education, politics, the workplace, religion, Latino heroes, farmworkers and Ramos’ first-person account of life in East L.A.

Beginning our research, we fanned out across Southern California. In some cases, a string of interviews would hit a dead end, and we would start anew. By the end of our project, we had conducted more than 1,000 interviews. We asked tough, probing questions, among them: Why is the dropout rate so high for Latinos? Are Latinos being held back in the workplace? Will Latinos someday become a potent political force?

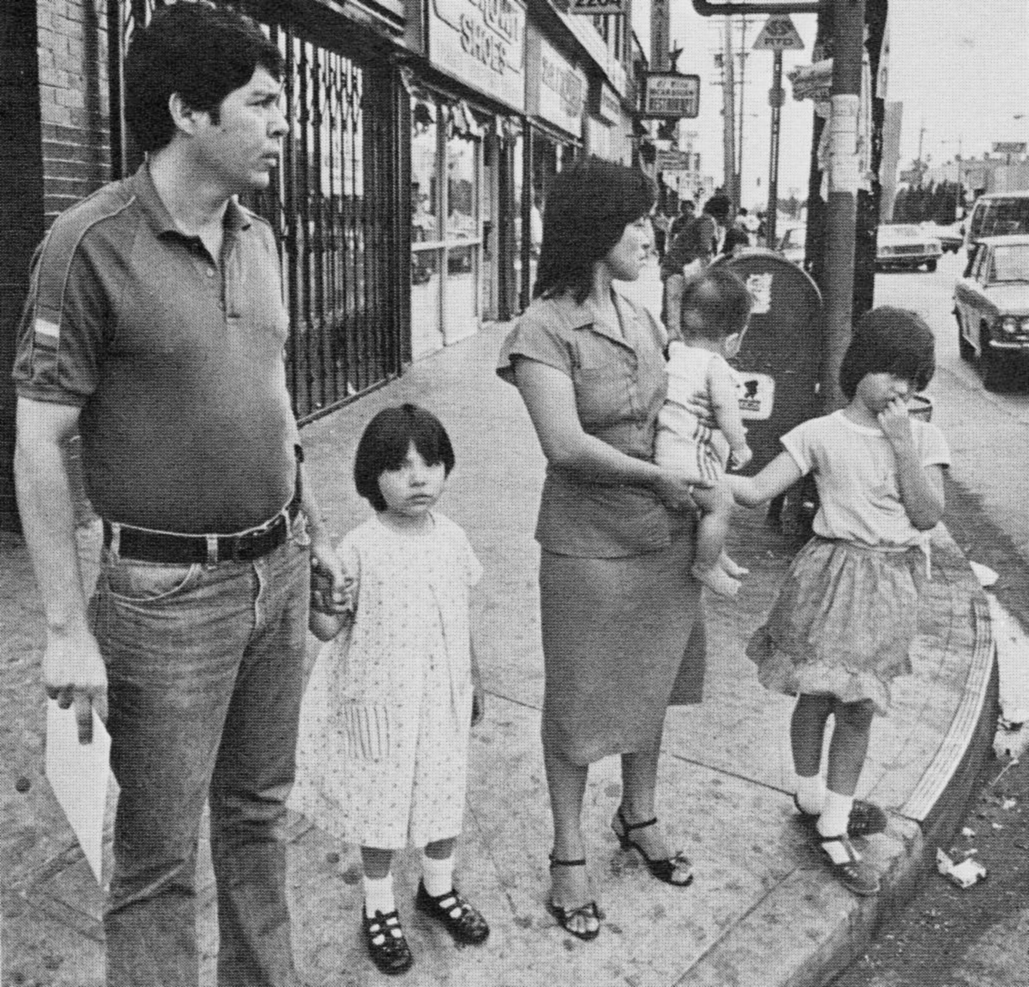

For my story on diversity within the Latino community, I went to the Central American community of Pico-Union, a densely packed neighborhood just west of downtown L.A. I was jarred to learn that as many as 300,000 Salvadorans, 100,000 Guatemalans and 50,000 other Central Americans lived in central L.A. It should have come as no surprise; after all, people were desperately fleeing the civil wars, unrest and grinding poverty of Central America. But sometimes reality does not slap you in the face until you get out of the office and start reporting in the streets.

Other reporters found pockets of Latinos from Cuba, Puerto Rico, Colombia, Argentina and elsewhere in Latin America. Our plan to focus almost exclusively on “the Mexican American experience” took a sharp turn. We acknowledged the new reality by informally renaming our “Chicano project” the “Latino series.”

Interestingly, the term “Latino(s)” was just gaining currency. Although most news media shunned the term, the Times adopted it in its stylebook of 1979. Del Olmo and I had made a case for its use as a generic term, instead of the bureaucratic-sounding “Hispanics” that had been adopted by the U.S. Census Bureau. The Times was the first large newspaper to adopt Latino(s), and the term slowly made its way across the country and into the pages and broadcasts of major East Coast news media.

As we conducted our series interviews, we also prepared questions for an opinion survey to be carried out by the Los Angeles Times Poll, headed by I. A. “Bud” Lewis and Susan Pinkus. Dr. Leobardo Estrada of UCLA, a former Census official, offered advice on the poll’s design.

The poll turned out to be a milestone because at that time, California Latinos had rarely been surveyed in sufficient numbers to provide statistically meaningful results. Thus, by design, 568 Latinos were surveyed, more than a third of the nearly 1,500 Californians polled.

The poll questions covered typical factors: employment status, religious affiliation and educational achievement. They also included hot-button issues and questions specific to our story topics. Our intent was to obtain hard numbers to bolster our reporting. Those poll results allowed us to write more authoritatively with quantitative results in almost every story.

The “Roots” saga

Robert Montemayor and Marita Hernandez were teamed on one of the toughest assignments, a story about the Mexican American historical experience told through the human drama of one extended family. It was only a few years after the Alex Haley “Roots” book and subsequent TV miniseries, and we often would refer to this project as our “Chicano roots” saga.

The story presented a difficult challenge from the start: How to find the right family. Hernandez described the process this way:

“Our chosen family would have to span several generations but still have ties to its original roots in Mexico; it would show progress across generations, displaying myriad personal struggles with all the dramatic turns of a telenovela; its members would represent a variety of social and educational strata; and would have lived through, perhaps participated in, the various twists and turns of Latino history in the Southwest.”

Hernandez and Montemayor talked to a number of potential subjects for the story, only to be disappointed at every turn. Finally, they reached out to an assistant dean at L.A.’s Occidental College, William Estrada. His family was a great fit.

A snag threatens story

“As we began interviewing members of the family, mining their memories and lives, we unearthed a treasure trove of experiences that reflected the bigger story,” Hernandez recalled. “But about halfway through the interview process, we hit what appeared to be an unsurmountable snag. Robert and I panicked. We knew it would be nearly impossible [because of the deadline] to start the process all over again with another family.

“Estrada, who had opened the doors to the homes and lives of so many of his relatives, threatened to slam them shut unless we agreed to new terms. In a crisis of faith, perhaps, as he became aware of the intense spotlight we were focusing on his family, he insisted over the phone that we allow him control over the story’s content before publication. As reporters, we knew this was untenable: He was asking that we break one of journalism’s strongest tenets. It would be censorship, pure and simple.

“Filled with trepidation, Robert and I met with Estrada. But we stood our ground: We threatened to pull the plug ourselves unless he agreed to our terms. At the same time, we offered reassurances of our good faith, reminding him that as Mexican Americans, we were in essence telling the story of our own families. He conceded and interviews with family members continued.”

Matriarch of extended family

Told across three generations, the story traced an extended family’s journey along the well-worn path of migration from Mexico to the U.S. Arcadio Yniguez, the family patriarch, traveled to Chicago during the Mexican Revolution in search of a job. He met and married Guadalupe Salazar, another Mexican migrant. Later, the couple split up and Guadalupe moved to Los Angeles, where she became matriarch of her extended family.

The family’s hardships and accomplishments mirrored the history of Mexicans and their descendants in California. The family struggled through the harsh days of the Depression. During World War II, a son went off to fight the Germans only to return home and find that he could not buy a home in a neighborhood of his choice because, he was told, Mexicans were not allowed. Guadalupe saw her grandchildren begin to push against those barriers as they were swept up in the politics of the Chicano Movement. Some gained college educations and entered the middle class, two of them—William Estrada and a cousin—as college administrators.

In researching her story, Hernandez had traveled to Nochistlán in central Mexico, the hometown of the family patriarch. José Galvez, our lead photographer, traveled with Hernandez. He photographed young girls dressed in white, framed against a dark archway of a Nochistlán church. His stunning image became our front-page photo when the “roots” story, the first of the series, was published.