The journey to a Pulitzer begins each year across the U.S. as news organizations prepare entries to showcase their best journalism. Initially endowed by publisher Joseph Pulitzer (1847-1911), the prizes were first awarded in 1917 and also honor work in letters, music and drama. They are conferred by Columbia University on the recommendation of the Pulitzer Prize Board.

In January 1984, nearly 1,200 entries landed at the Pulitzer Prize Administrator’s Office at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. Among them were 28 entries in various categories from the Los Angeles Times. They included a long shot, our 1983 Latino series.

The Pulitzer board selected prominent journalists, including former prize winners, from across the country to judge the journalism entries. The jury for Public Service, chaired by Robert C. Maynard, Oakland Tribune editor/publisher, began evaluating its 96 entries on March 5. Other jury members were Loren Ghiglione, editor and publisher of The News in Southbridge, Mass., and three managing editors: David V. Hawpe of the Louisville Courier-Journal, Sue Reisinger of the Miami News and Frank Wright of the Minneapolis Star and Tribune.

As I retraced the path of the Latino series to the Pulitzer Prize, I ran across a little mystery. The series was sent to Columbia as an entry in the Local Investigative/Specialized Reporting category. How did it get to the Public Service category?

A fateful switch

It took some digging by staff of the Pulitzer Prizes Administrator’s Office at Columbia to find the explanation for the switch. The clarification finally came from Deputy Administrator Edward M. “Bud” Kliment:

“In 1984, newspapers were allowed to submit work in only one category. For some reason, an LAT entry on the military-industrial complex was inadvertently submitted twice, entered in both Public Service and National Reporting. When informed of the duplication, Bill Thomas decided to keep that entry in National Reporting and move the LAT entry on Latinos from Local Investigative/Specialized Reporting to Public Service.”

What? The editor who once refused to enter our Latino series suddenly does a reversal and nominates it for the biggest Pulitzer of them all.

With that change, the Latino reporting entry faced something of a disadvantage. Only 10 stories could be submitted with an entry in the local category. When the Latino series went to Public Service, it was pitted against newspapers that had showcased a broader range of work, submitting up to 20 articles per entry. But the Latino series had an ace in the hole. As supplementary material, we had submitted the 133-page reprint book that contained every story, every photo and every graphic element from the series. That allowed the jury to see the full range of our work.

Jury selects three finalists

The 1984 jury chair, Maynard, was a close friend. As the nation’s most prominent advocate for media diversity, Maynard would have been drawn to our series. But he was also a thoroughly fair person and he would have been drawn to other examples of exemplary journalism. Interestingly, Maynard’s jury met in the same hall where he and five others of us had been told 10 years earlier by Fred Friendly that his program to train minority journalists would be ended.

Two of the other Public Service jury members generously shared their recollections of jury deliberations. Both Loren Ghiglione and David Hawpe were dedicated national leaders in the campaign to bring diversity to both news coverage and newsroom employment. It must have been a gratifying surprise for Ghiglione and Hawpe to discover among the entries an example of the coverage they and others had been advocating.

“I remember the L.A. Times series as my first choice,” Ghiglione, now a Northwestern journalism professor, said in an email. “I grew up in Claremont, Calif. I didn’t recall the LA Times as an especially progressive paper in an earlier era. I remember being impressed in 1984 by the wide-ranging reporting by the LA Times team and by the fact that the team was Latino. To me, the series really was a landmark piece of journalism.”

Power of diverse staffing

Hawpe wrote in a recent email: “I do remember the discussions we had on the Public Service jury. We all felt it was a landmark effort, demonstrating the power of diverse staffing to produce unique insight into local issues. We also thought it was impressive in the breadth and depth of the effort. I thought it should win.”

Maynard, who died in 1993, never shared with me any details of his Pulitzer involvement regarding the Latino series. Efforts to reach Wright were not successful. Reisinger said she had no recollection of the particulars of the judging except that she was very ill with the flu during that process.

At the end of the jury’s deliberations, it was time to submit a report to the Pulitzer Board with the three strongest entries, its three finalists, listed in alphabetical order. Below is the jury’s report, dated March 7, 1984, to the Board:

2. Fayetteville [N.C.] Times (“And justice for all?”): This series exposes the failures and the favoritism in the local system of justice. Once again, it is thoughtful and compelling work that took courage and conviction, especially by a newspaper of smaller circulation (23,500) and limited resources.

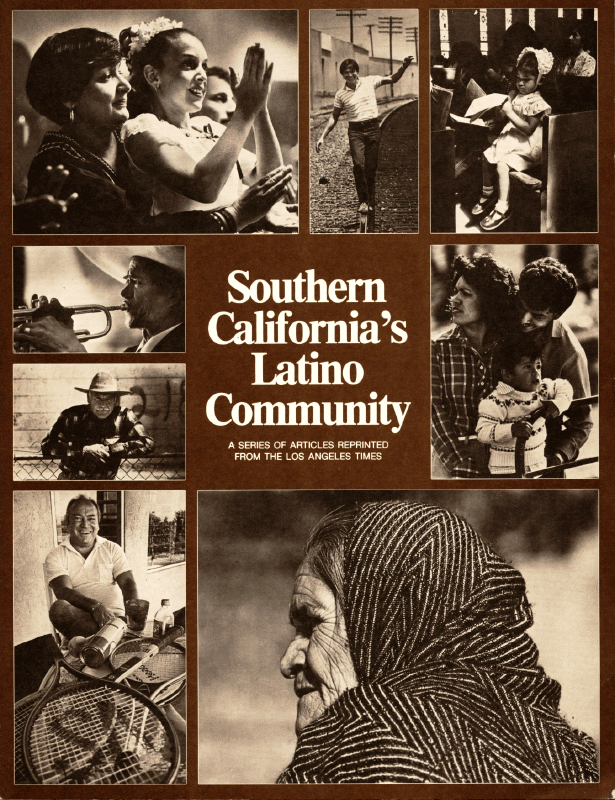

3. Los Angeles Times (“Southern California’s Latino community”): This landmark piece of journalism examines in impressive detail the life and changing times of the Latino community in California. Most impressive of all is the fact that The Times was able to field a task force composed entirely of Latino editors and reporters to provide a unique view of one of America’s most important emerging ethnic groups.

The Free Press’ hard-hitting investigative series was just the type that typically won for Public Service. After all, it brought to light car safety issues that potentially affected millions of Americans. Most people, I would guess, would have considered the Detroit entry as the absolute favorite to win the prize. Our series had reached a milestone in making it to the Final Three, but it was still a long shot.

The Pulitzer Board’s decision

The board met April 5 and 6 in the World Room to make its choices. Its members, all male, included such distinguished journalists as Eugene Patterson, editor of the St. Petersburg Times, Eugene Roberts, executive editor of the Philadelphia Inquirer, and Osborn Elliott, onetime Newsweek editor and then Columbia journalism school dean.

Columnists William Raspberry and Roger Wilkins, the board’s first African American members, had joined the board a few years earlier. Three academics were also on the board. No one from the L.A. Times was on the board, but David Laventhol, publisher of the Times’ sister newspaper, Newsday, was a member. By rule, he left the room during deliberations and votes concerning the L.A. Times because both Newsday and the Times were part of Times Mirror Co.

No records exist of the board’s deliberations. Via email, I reached Michael G. Gartner, a board member who in 1984 was president and editorial chairman of The Des Moines Register and Tribune. “Within the Board,” Gartner said, “there were often vigorous and spirited discussions and debates.… In those days, we would discuss stories and entries on Day One, but we never took formal votes until Day Two. And the votes were formal—and often very close. Many a person has come within one vote of winning a Pulitzer.”

Public Service criteria

With three finalists in the running for Public Service winner, the board members likely considered each against the category’s long-standing criteria: “For a distinguished example of meritorious public service by a newspaper through the use of its journalistic resources, which may include editorials, cartoons, and photographs, as well as reporting.”

The Latino series certainly had used a broad variety of the newspaper’s resources to provide a service to its readers and public:

Thirteen Mexican American writers produced 18 major stories, seven sidebars, one column, an editorial and five oral histories.

One hundred and nine photographs were published, shot by four team photographers and four other Times photographers.

Artists created 21 informational graphics and maps.

In addition to 1,000 reporter interviews, nearly 1,500 Californians were surveyed by the L.A. Times Poll.

The series was published simultaneously in Spanish by La Opinión newspaper to reach a wider audience.

More than 4,000 reprint books were distributed to the community.

These bullet points speak largely to quantity. I believe the quality was there too, with in-depth stories rich with voices, anecdotes and experiences. The series opened a large window for readers into the hearts and daily lives of the region’s Latinos.

As reporter Virginia Escalante said, it “presented the Latino community in a way that hadn’t been done before with authentic voices, with heart, through our own eyes.”

Clearly, board members would not have read all the pieces in the series. But I am quite certain they read the letter that introduced the entry. That intro skillfully described the bullet points above in expanding on the “what,” the “how” and, most important, the “why” of the series. The reprint book turned out to be significant. During jury deliberations, Hawpe recalled, “It did have an impact on my enthusiasm for the work as a whole.”

In our letter summarizing our series, we stated that readers and officials had affirmed that the series had “enhanced the public’s understanding of complex social issues and helped clear away some stereotypes. We also pointed out in that summary what a Times editorial summing up the series had said:

“The articles achieved their goal. All contributed to opening up a community that, despite being an integral part of the history and daily life of this area, too often is seen as mysterious or even threatening by the rest of Los Angeles. The Latino series clearly showed that this fearful attitude, the result of Anglo indifference rather than hostility, is mistaken.”

Reflecting on the Pulitzer board’s decision, Gartner said: “I have little recollection of the particulars of the 1984 Pulitzer Prizes, but … I do recall that the [Latino] series stood out—mainly because nothing like it, by subject or magnitude, had been done before. Or if it had been, we didn’t know about it.”

Board selects our series

In the end, the board awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Meritorious Public Service—considered the highest award—to the Los Angeles Times for the Latino series. Citing the extensive reporter interviews and the Times Poll survey, the board said:

“The resulting articles, which blended autobiographical accounts and other forms of personalized reporting with in-depth analysis of the problems, achievements and changing nature of the Latino community, were hailed as a landmark effort by experts on the subject.”

In words that echoed, in part, the series’ concluding editorial, the board praised the series “for enhancing the understanding among the non-Latino majority of a community often perceived as mysterious and even threatening.”

Gene Roberts, who led the Philadelphia Inquirer to 17 Pulitzers in 18 years, recused himself from the 1984 Pulitzer Board deliberations because the Detroit Free Press was a finalist and both it and the Inquirer were Knight Ridder newspapers. But he said this in a recent email:

“Your Latino series was a public service and richly deserved to win the Pulitzer Prize for public service. To me the award should not be tightly categorized but should always go to whoever best served the public in a given year. And that was your series in 1984.”

After the Pulitzer board makes its decisions, the winner’s names are supposed to be kept in confidence. The operative word is “supposed.”

“Leaks” about the Pulitzer

One day in early April 1984, I rode the elevator down from the 10th floor cafeteria. When the doors opened on the third floor, higher education writer Anne Roark blurted out something like: “You’re gonna win a Pulitzer.” Stunned, I asked her to tell me what she knew. A source had told her, she said, that the Latino series had been chosen to win a Pulitzer.

Still stunned, I asked her not to tell any series team members because I knew that if it weren’t true, we’d all be devastated. Thomas was on vacation, but one of his assistants phoned him with Roark’s news. “He just called me back and [is] about to die,” Roark wrote to me in a note while I was away from my desk.

I did not share with team members what Roark had told me. Within a few days, on April 11, several of our team members headed to Washington, D.C., for the first conference of the National Association of Hispanic Journalists. Moran, Ramos, Del Olmo and I all had roles in the group’s formation, and we enjoyed meeting with colleagues from around the country.

Ramos later recalled this exchange as he and José Galvez were out jogging one morning.

Galvez: “Have you heard the rumor?”

Ramos: “What rumor?”

Galvez: “We're gonna win the big one.”

At that point, a street light turned green and Galvez took off, leaving Ramos at the corner.

“Win what? Win what” Ramos yelled. He ran for two blocks to catch up with Galvez and asked again: “Win what?”

Galvez looked at Ramos and said, “Win the big one, the Pulitzer Prize.”

“No way.” That’s all Ramos could say.

Back at the hotel, they and other team members got word to be back in the newsroom on Monday morning. Times editors had received confirmation through a “leak” that we, in fact, had won a Pulitzer.