Two years after Watts, during a long, hot summer, the fires of urban rebellion erupted again, first in Newark and then in other cities. President Johnson appointed a national commission to study the causes of the rioting. In issuing its report in early 1968, the commission, headed by Illinois Gov. Otto Kerner Jr., took sharp aim at both federal and state governments for botched policies on education, housing and social services.

The mainstream media also were targeted for harsh criticism. “The press has too long basked in a white world looking out of it, if at all, with white men’s eyes and white perspective,” the Kerner-led report stated. “The journalistic profession has been shockingly backward in seeking out, hiring, training, and promoting Negroes.”

Without mentioning Latinos or other minorities, the report concluded: “Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal.” That statement was typical for that era when Latinos, Asians and Native Americans were rarely a part of the national dialog.

Dr. King is assassinated

A month later, on April 4, 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. Within days, more than 100 cities erupted in rioting and more than 40 people were killed.

The effects of the Kerner Commission admonitions to the news media are not fully known. Many newspaper editors clearly paid little attention, and newspapers continued to be all-white institutions in a majority of U.S. cities. Other newspapers hired one, two or a handful of journalists of color, primarily African Americans.

The Kerner report and the widespread rioting motivated one man to take action. Former CBS President Fred Friendly, then teaching at Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, moved swiftly in 1968 to establish a training program for minority reporters. For seven years, veteran journalists taught aspiring journalists about the business and arranged jobs for them upon completion of the summer program.

In 1974, I was fortunate to join with a multi-racial group of journalists to provide training at Columbia for 14 African Americans, Latinos and Asian Americans. Upon the successful completion of the 11-week program, faculty and reporters gathered at the Journalism School’s third-floor World Room for a graduation ceremony. Then came the bad news: Friendly said the program would no longer be held. Our job is done, Friendly said, insisting it was the task of colleges and the news media to take over the job of training and providing jobs for minorities.

Reviving a crucial training program

Those of us on the summer faculty—Robert C. Maynard, John L. Dotson Jr., Roy Aarons, Earl Caldwell, Walter Stovall and I—took sharp issue with Friendly. Even with the infusion of his program’s graduates, U.S. newsrooms were still 98% or 99% white. With funding from major newspaper groups and foundations, we established the Summer Program for Minority Journalists at UC Berkeley. During 14 years, more than 200 journalists received training there and went off to reporting jobs across the nation. Three graduates, Virginia Escalante, David Reyes and Louis Sahagun, went to the L.A. Times and later became members of our Latino series team.

Our group incorporated as the Institute for Journalism Education (IJE) in 1977. We added programs for copy editors at the University of Arizona and for management at Northwestern University. IJE soon became an agent of change. In a 1978 milestone, IJE sponsored the National Conference on Minorities and the News in Washington, D.C. Our IJE leaders—Robert C. Maynard, his wife, Nancy, and Roy Aarons—lobbied editors at a concurrent conference of the American Society of Newspaper Editors (ASNE). As a result, the ASNE established the Year 2000 Goal, stating that by the end of the 20th century, the percentage of minority journalists would be at parity with the percentage of minorities in the nation. The ASNE also approved a national census of daily newspapers. Each year, newspapers were asked to submit statistics on the number of racial minorities on staff. The survey, which continues today, later also began asking for statistics on women on staff.

In 1993, after Bob Maynard’s death, IJE was renamed the Robert C. Maynard Institute for Journalism Education, and the institute is still engaged in diversity issues. (Link to “The First 30 Years of MIJE: Making Newsrooms Look Like America.”)

We so-called minorities also began taking steps to change the makeup of the nation’s newsrooms. Del Olmo and I were among founders of the nation’s first organization of minority news professionals. In 1972, our group became incorporated as the California Chicano Newsmen’s Association. Shame on us males for doing that. It was only after a few women joined our group that we got rid of the sexist “Newsmen” and renamed it the California Chicano News Media Association. Later, national organizations of African American, Asian American, Native American and Hispanic journalists were formed.

But overall, the newspaper industry failed miserably in achieving the Year 2000 Goal. Even today, people of color make up only about 17% of newspaper staffs and women of all colors represent about 38% of newsroom professionals. Nonetheless, the concept of newsroom diversity and inclusive news coverage became part of the industry dialog. Significant numbers of journalists of color were hired, including several who became key members of the Latino series team.

Nearly all-white newsroom

When I reported for work in October 1970, the Times contained about as much color as a loaf of Sara Lee white bread. You could count the number of journalists of color on two hands. You could count the number of journalists of color on two hands. We were like the brown crusted edges of the nearly all-white newsroom. “Diversity was a concept that had not yet been invented,” recalled Drummond, the African American reporter who had been hired in 1967.

By the early 1980s, the Times had finally assembled a small corps of outstanding African American reporters. Still, it had not learned the lessons of diversity. None of those reporters was involved in a story that created a powerful blow-back from the black community. The story became known, infamously, for its subject matter—“the marauders.”

Many years later, in retirement, Bill Thomas talked about what he saw as the genesis of the story in an interview with author Roy J. Harris Jr. for the 2007 book “Pulitzer’s Gold.” Thomas said he was intrigued by a criminal pattern, which he said dated “from around the time of the Crusades,” of impoverished men raiding and robbing the rich and quickly escaping.

Times article comes under fire

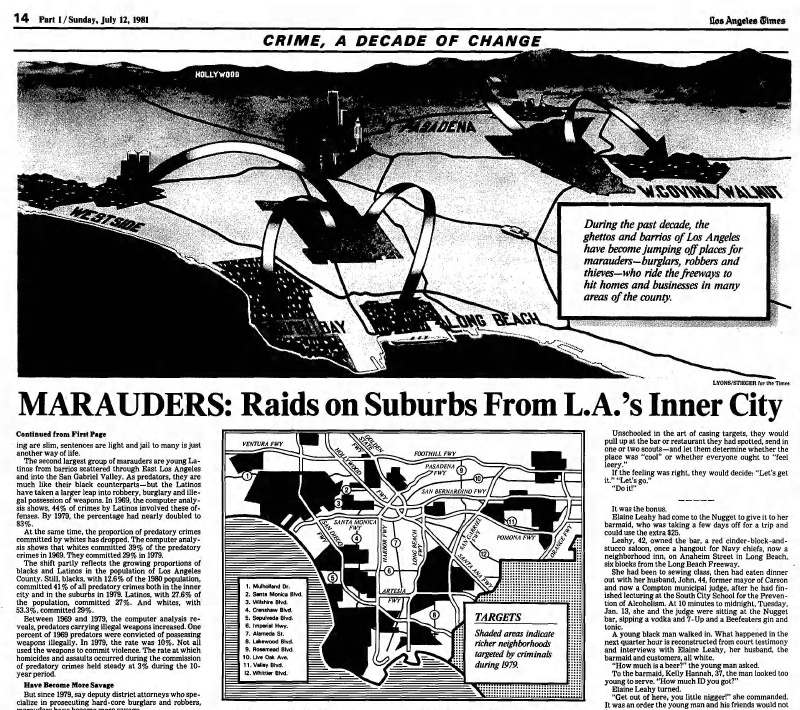

Two reporters, Mike Goodman and Richard E. Meyer, both white, were assigned to explore the subject. After months of reporting, they wrote about inner-city blacks and Latinos, particularly black men from South L.A., who carried out robberies in the suburbs and then sped away on freeways. Instead of referring to the men as robbers or thieves, the stories labeled them “marauders” and used such inflammatory descriptions as “savage,” “predators” and “the Nairobi Highway.” The article ran at the top of the front page—even above the “Los Angeles Times” nameplate—in a space only rarely used for extraordinary news stories.

Soon after the article appeared in 1981, the newspaper came under verbal attack from spokesmen for the black community. A Times article on an outdoor rally in the Crenshaw neighborhood reported that the newspaper had been accused “of maligning the black community in its article … about inner city criminals who prey on surrounding suburbs.”

Recalling the marauder story later, George Ramos told filmmaker Roberto Gudiño: “It just reinforced that stereotype that people of color are marauders, that they're rapists, that they're killers, that they are marginalized people of society.”Recalling the marauder story later, George Ramos told filmmaker Roberto Gudiño: “It just reinforced that stereotype that people of color are marauders, that they're rapists, that they're killers, that they are marginalized people of society.”

Even before the marauder story, the Times was being attacked for its lack of staff diversity and biased, crime-dominated coverage of L.A.’s black communities. Little had been written about the Los Angeles Police Department’s troubled relationship with African Americans. The Times had done little reporting on an important community that had nurtured the career of Tom Bradley, L.A.’s first African American mayor.

In reaction to all this, an idea emerged at the Times. Why not do a series about the true black experience in Los Angeles? With the staff’s talented African American reporters producing the stories, the 1982 series, titled “Black L.A./Looking at Diversity,” contributed to a better understanding of the region’s African American community. Thomas nominated it for a Pulitzer. It did not win a prize, but it set a precedent for a Times racial or ethnic group writing about its own community.