The pizza was hot. The beer was cold. About eight of us, Times staff members who were Mexican American, gathered in the Times’ satellite office in Downey, from which I led the Southeast/Long Beach zone sections. On that February evening in 1982, we exchanged pleasantries and soon felt a sense of camaraderie among friends, among colleagues. One after another, we began expressing our dismay at how our newspaper covered the Mexican American community of Southern California.

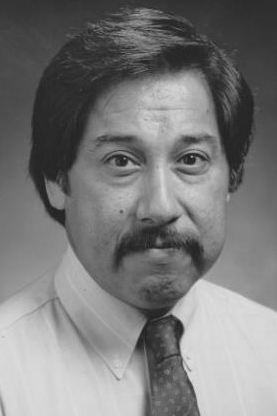

Although one-fourth of the region’s population was of Latino ethnicity, the Times had been excruciatingly slow in hiring journalists of color. Frank del Olmo and I lobbied hard for the hiring of more Latinos to help cover the region’s largest minority group.

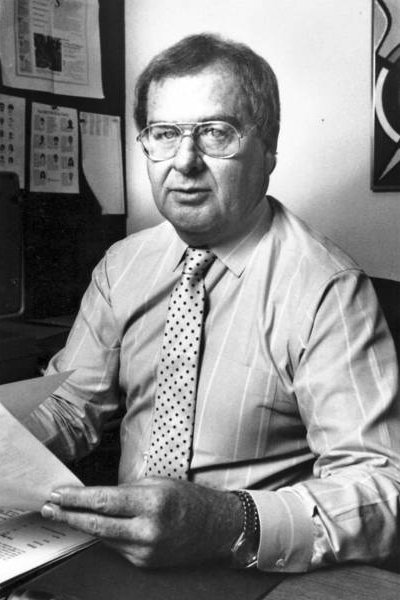

In the late ’70s, the Times went on a small hiring spurt. Marita Hernandez, Robert Montemayor, George Ramos and David Reyes were hired between 1978 and 1980, followed by Julio Moran, Victor Valle, Louis Sahagun and Nancy Rivera. José Galvez and Rick Corrales joined the photo staff. The increased talk nationwide about newsroom diversity no doubt played a part in the hiring decisions, along with the 1981 promotion to Metro Editor of Noel Greenwood, a white former education reporter who took steps to diversify his reporting staff.

The hiring burst helped form a critical mass of Latino staff members. By 1983, we even had enough staff members to field a softball team, the Chicano Cubs. We often ran into one another at meetings of the California Chicano News Media Association but not at the Times, where we were scattered in sections from San Diego and Orange County to Central L.A. and the San Fernando Valley.

As the pizza grew cold that night, we discussed, we laughed, we complained, we cursed, we brainstormed and finally we agreed.

George Ramos, a hard-nosed reporter, was the most outspoken. I remember his saying: “We keep seeing the same damn stories in the paper. About crime, gangs, illegal immigration. We want to tell our stories.” Others made their own statements and heads nodded.

“Not their kind of newspaper”

We complained that Publisher Otis Chandler, in a 1978 TV interview, had basically written off Mexican Americans and blacks as Times readers when he said: “It’s not their kind of newspaper. It’s too big, it’s too stuffy. If you will, it’s too complicated.”

Things got heated for a while at that Downey meeting. Then we took a breath and stepped back a bit. We talked about how society in general perceived Mexican Americans. People of Mexican origin had been the earliest settlers of Los Angeles and throughout the Southwest. Yet, over the years, many Mexican-origin people had been pushed to the margins. In the eyes of many Californians, Mexican Americans had become “the other” in our own land.

There was an unwritten class and color distinction. If you were upper income, lived in Pacific Palisades and had relatively light skin, you “fit in.” In fact, people might consider you “Spanish,” a far more acceptable designation in the eyes of many whites. However, if you were from a working-class family and dark-skinned, chances were good that you’d be considered a foreigner, an “other.”

Many years later, Ramos talked about growing up in East Los Angeles and feeling confused about how he had been perceived. “I started to realize that these [white] people, they kinda knew who we were, but they thought we were like, foreign—from a different planet. And I kept saying, ‘No! I do the same things that you do.’ ” The young Ramos was perplexed about why he would be considered anything less than a 100% American. He was born in East L.A. to an honorable, patriotic family. His father and uncles had fought in the U.S. military against the Japanese in the Pacific and the Germans in Europe during World War II. “I remember my dad being called a wetback, being called a spic.… I remember as a kid being called a nigger. And I remember asking my dad, ‘That’s not a good name, why do they call us that?’

“ ‘Well, they just don’t know us,’ he would say. ‘Don’t talk back to those name-callers, leave it alone.’ ”

But even as a boy, Ramos told filmmaker Gudiño, he had always thought: “No, we need to explain who we are.” And that is the attitude he took to our discussion on that 1982 evening.

Our group kicked around ideas on how to proceed. Someone suggested a petition to the editors, citing our grievances, but that idea was quickly dismissed. Finally, we agreed to propose a list of stories about Mexican Americans that were so original and compelling that our editors could not resist.

The plan moves forward

We met again a few weeks later, this time in Ramos’ apartment off Sunset Boulevard in the Silver Lake neighborhood. It was already dark when we entered his apartment, but it was even darker inside. George, always the jokester, said he liked to keep his light bills low. He finally turned on a lamp, but it must have had a 40-watt bulb. In semi-darkness, we felt our way to a well-worn couch and chairs.

By this meeting, the reporters’ story ideas had started to jell. Some had carried these ideas in their heads for years, unable to pursue them because they were expected to produce only stories from their section’s own geographical beats.

We envisioned that our stories would be published from time to time as they were ready. No one talked at this point of a Latino series.

Stereotypical subjects

We requested a meeting with Metro Editor Noel Greenwood, but he asked that we talk instead with David Rosenzweig, the city editor. At that March 12 meeting’s start, I said: “We don’t want to belabor the negative because we are here in a very positive spirit, but we feel that much of the Times’ coverage [about Mexican Americans] has focused on a few stereotypical subjects, such as gang violence and illegal immigrants.”

We complimented Greenwood for the recent hires of the Latino reporters. “No other paper in the country can match the talent and experience of the Chicano journalists in this room,” I stated. However, I pointed out, the Times was like a sports team using key players out of position.

We wanted our chance to inform the public about the full dimensions of the Mexican American experience, we told Rosenzweig. Reporter Marita Hernandez then discussed story ideas we had developed. Our articles will be thoroughly reported and will be told not solely through statistics or “experts,” we said, but with on-the-ground people stories.

Rosenzweig seemed intrigued and grew even more interested when we gave him a full list of proposed stories. He was pleased with our presentation and said he would report to Greenwood. We left the meeting pleased too. We did not hear from Greenwood for a few weeks and were getting nervous about whether our story ideas would see the light of day. Finally, word came that Greenwood had embraced the story ideas. He said he wanted them produced as a series. Oh no, we thought: The series will be published in a one-day special section, and the unacceptable status quo will return. But Greenwood reassured us that the series would be a serious journalistic endeavor, published over an extended period. On September 20, 1982, what we then called the “Chicano Project” got the official green light. Greenwood met with Ramos and me to outline his project plan, which had been approved by Bill Thomas. And because the project would entail significant added costs, Publisher Tom Johnson had likely signed off on it too.

Greenwood designated Ramos and me as series co-editors. Ramos was then an assistant city editor in the Orange County edition. I headed the Southeast/Long Beach suburban sections but was new to local coverage, having spent 11 years on the international news desk. My experience teaching at the Berkeley minority training program had enhanced my ability to work one-on-one with reporters and strengthened my resolve to speak truth to power.

Greenwood strongly emphasized that he wanted original, creative approaches to stories.

“Don’t try to reinvent the wheel,” Greenwood said, words that we would often repeat to our reporters in the coming months. He arranged to have reporters who were assigned to outlying offices start work exclusively on the project after New Year's Day 1983.

Not everyone in the newsroom was enamored of the plan for the special project. Robert Montemayor recalled reporters griping: saying things like: “Why can’t this be done as part of the regular rigors of journalism on a day-to-day basis?” Montemayor’s retort was dead-on: “Well, the fact of the matter was they weren’t doing it.”

Others questioned why the project would be carried out exclusively by Mexican American reporters and editors. A few wanted in. We argued that we’d come up with the story ideas and that we had the cultural knowledge, Spanish-language ability and overall expertise to best deliver the stories. Our arguments prevailed.