(Continued)

Five Latinas’ oral histories

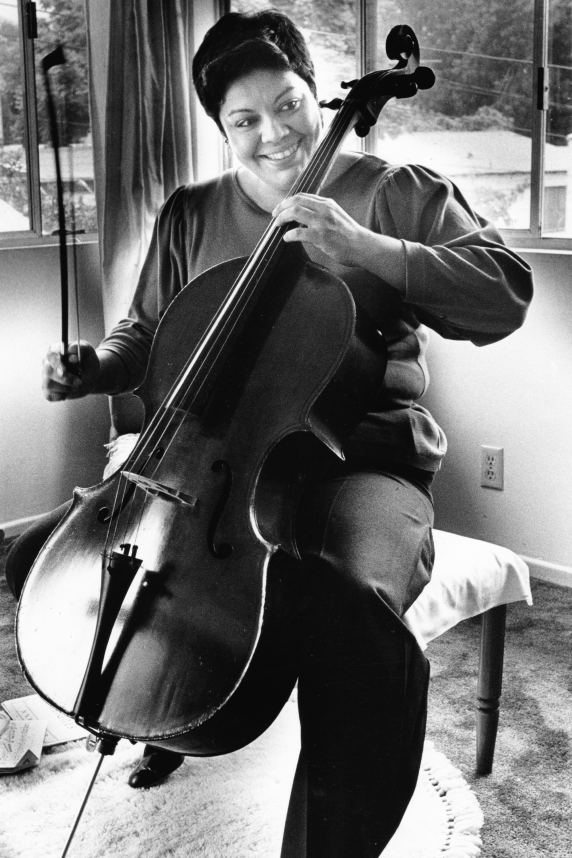

We wanted to do a story about women—las Latinas. But instead of sketching an overview of a mega subject, Escalante and Victor Valle suggested letting five women speak for themselves in an oral-history format. We knew their stories would be symbolic of the lives of countless number of Latinas. The five were a longtime peace activist, a manager in the corporate world, a union organizer for female garment workers, a housewife whose family—all U.S. citizens—had been deported to Mexico during the Depression, and a Chicana activist who was a poet, writer, actress and musician.

The women, photographed by Almeida, spoke of hardship, of bearing the dual burdens of racism and sexism. But they also spoke proudly of successes, of standing up for their rights and of love for their culture and families.

Overlooked artists and writers

Victor Valle’s background as a poet, writer and editor of art and literary magazines made him eminently qualified to write about the evolving Chicano art and literature movements. Yet William Wilson, the Times’ senior art critic, read a draft of the story and questioned “whether I was qualified to make the kind of interpretive judgments a critic could make,” Valle recalled.

Valle said he had anticipated that objection: He showed editors Times clips that revealed that the paper was about a decade late in “discovering” the Chicano mural movement. “My answer was accepted,” Valle said, “and I did not retract a claim that implicitly criticized the Times for perpetuating the cultural marginalization of the Latino community.”

In his piece, Valle quoted respected art scholar Margarita Nieto, who argued that “there is still a pathetic ignorance of Mexican and Chicano culture. This is one city where this should not be.”

Some Chicano artists talked about the lack of attention from the media and museum curators. Meanwhile, acclaimed painter Carlos Almaraz argued that it was time for Mexican American artists to stop blaming others. He insisted that “Chicano artists can grow only by learning to survive in the marketplace rather than depending on grants or the shelter of nonprofit organizations.”

Valle also produced a piece on Mexican American poets and authors who were starting to have an impact in the literary world. Some wrote in English, some in Spanish and some, notably Alurista, juxtaposed English and Spanish in poetry.

Catholics and protestants

Julio Moran, who was raised in Pacoima, the same San Fernando Valley neighborhood as Del Olmo, proposed the story about religion. “Since I am not Catholic, I wanted to write a story that debunked the myth that all Latinos are Catholic and also depict issues faced by Latinos who are not Catholic.”

In his piece, Moran observed that “Catholics seemed to take their religion as a cultural tradition. Protestants seemed to be more interested in the spiritual aspect.”

Church officials estimated that 90% of all Latinos—about 13 million nationwide—identified as Catholic. But as many of 80% of those were considered “lukewarm Catholics” who did not attend church services regularly or who participated in services with little commitment.

Citing L.A. Times Poll results, Moran also reported on a slipping away by Latinos from Catholicism to Protestant faiths.

The photography challenge

Moran’s religion story was accompanied by striking photos by José Galvez. One of the guidelines at that time required photographers to take “head shots” of people being quoted. Galvez had a different perspective. “To me the biggest challenge was to have the photography be more than just a series of portraits, of people smiling into the camera.” He met the challenge and more.

In the religion story, he shot worshipers of different ages and diverse denominations in prayerful poses that enhanced the storytelling quality of the article.

“I faced some resistance from the reporters and some editors about not photographing every single ‘talking head’ that was being interviewed,” Galvez recalled “Ultimately we got a decent mix, but if I had to do it over, I would have been more forceful on some of the images used.”

One good thing, Galvez recalled, was that he and the other photographers did their own editing and selected their best images. All the photography was shot on black and white film; after all, this was years before color photos became common in U.S. newspapers, and our project took place a decade before digital cameras.

Both Galvez and I wanted Monica Almeida and José Aurelio Barrera, two very young photographers, to use the project experience to further their careers. And it did. Barrera was hired as a Times photographer and later served as a staff photo assignment editor. Almeida described working on the series as a “life-changing experience.” She went on to an illustrious 24-year career as a New York Times photographer.

Like others on the team, Galvez had made an unorthodox entry into the newsroom. As a boy of 10, he took his shoebox into the Arizona Daily Star newsroom in Tucson to polish a reporter’s shoes. After that, he became a newsroom fixture, as he related in his book, “Shine Boy.” Mentored by Star photographers, he bought a camera at a pawn shop, studied journalism and went on to an exceptional photojournalism career at the Star and the L.A. Times.

Falling short on education

Robert Montemayor was a good choice to tackle the complex subject of how Latinos were faring in education. Growing up in the West Texas town of Tahoka was harsh, Montemayor told filmmaker Gudiño. “I remember going out in the summertime with mom and we’d basically chop cotton for 40 cents an hour, so $4 a day.… And it was a struggle. You constantly ran into this racism and discrimination thing. It just hung in the air all the time.”

His father warned him that he’d have to work hard to be successful and that things would not always be fair for Mexican Americans, Montemayor said. He traced his determination to do well to his parents’ guidance in a challenging environment. After graduation from Texas Tech, he won awards at the Dallas Times Herald for investigative reporting.

For his Latino series assignment, Montemayor pored over education statistics and interviewed dozens of students, teachers, principals and education specialists to produce one of the series’ most important stories. With the population surging, Latinos made up one-fourth of the state’s public school enrollment and half the enrollment in L.A. city schools. As competition with other industrial nations revved up to produce the “best and brightest” workforce, California was failing miserably.

Yes, individual Latino students excelled and made it into top colleges. However, the overall education picture was depressing. Almost half of Latinos in public secondary schools were dropping out across the state. And even those finishing high school were often deficient in their achievement.

Why? That was the obvious question, and Montemayor heard a plethora of answers from state education officials. Some students from Spanish-speaking homes were not successfully transitioning to English in school. Educational opportunities at schools with high Latino enrollment were not at par with those at other schools. In some cases, Latinos were seen by educators as “products of a culture of poverty” and thus were tagged as apathetic, fatalistic, not goal-oriented, unacculturated and culturally deprived. These attitudes set up low expectations and resulting low achievement for too many Latino students.

Professors who studied the K-12 education issue told Montemayor that funding was not being directed in ways to achieve better results. A sidebar story on university education by Louis Sahagun made a similar point regarding revenues from the state’s taxpayers: More bachelor’s and master’s degrees were awarded in 1981 to students from other countries than to Latinos, who made up one-fifth of California’s population.

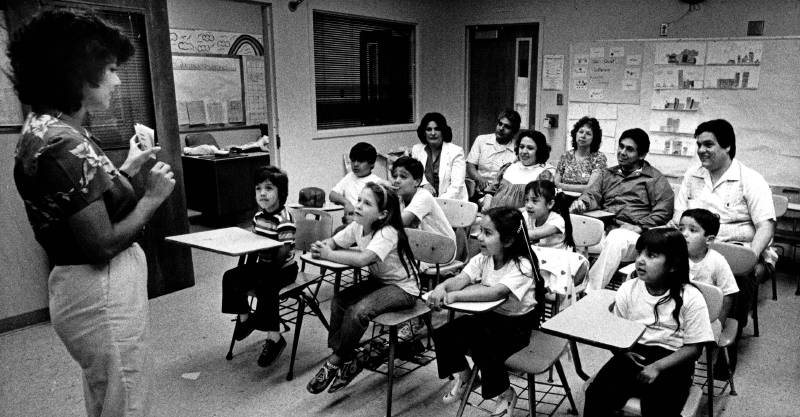

In another sidebar, Montemayor described Latino parents’ pressure groups getting involved in the day-to-day functioning of schools. Significantly, large numbers of parents were attending English as a Second Language classes and becoming more sophisticated in education matters. Looking back, it is clear these actions foreshadowed greater involvement of Latinos in grass-roots campaigns that challenged the status quo.

Diversity in Latino communities

I was so involved with conferring with the reporters and editing their stories that I had neglected reporting on my own story on Latino diversity. Early in May, I started getting nervous about my deadline.

Then, at a family outing during a Cinco de Mayo celebration, I struck up a conversation with a group of men wearing T-shirts of the same design. They told me they had started a Saturday morning school for their children so they could gain an appreciation for their Mexican American culture and learn Spanish. The parents were chagrined that even with their Chicano Movement activist background, they had not passed along their heritage and Spanish ability to their sons and daughters.

I attended one of the group’s Saturday morning classes at the school along with photographer Aurelio José Barrera. Bingo! I knew instantly that I had good material to lead my story.

Undocumented Salvadorans

That morning at the school invigorated me. I intensified my reporting, meeting with a director of a Central American refugee center. He introduced me to the Romeros, an undocumented Salvadoran family. Joaquin Romero, a news photographer, had been wounded by government soldiers in El Salvador and had fled the country for fear the troops would kill him. He came to the U.S. for medical treatment and overstayed his visa. His wife and two older children then crossed the border illegally in a harrowing journey. They waded a garbage-filled river, climbed a series of fences, jogged for hours and hid as helicopter roared above.

I was reluctant to use the family members’ names for fear they would be deported, but they urged me to do so, thinking the newspaper story would give them “some type of documentation.” (I lost track of the Romero family years later, but I believe they later received legal immigration documents.) Their experience offered a microcosm of what life was like for L.A.’s Central American communities.

Of the more than 2 million Latinos in Los Angeles County enumerated in the 1980 Census, 80% were of Mexican origin with the remainder Central American, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Dominican or South American. Diversity was also evident among the Mexican-origin population: Some traced their roots back several generations and others were recent immigrants.

For my story, I juxtaposed the activist Chicano parents of the Saturday school with the Romeros. For a third element of focus, I described two Mexican American couples who lived in suburban Hacienda Heights, a suburb often called “the Chicano Beverly Hills.” Both couples retained close ties to their roots in East L.A. and to the Latino community through their jobs. Throughout my piece, I discussed the issues of assimilation and the retention of language and culture.

In a sidebar, I relied on Times Poll results that sampled public opinion on a hot-button issue. Congress was considering bills to grant amnesty to unauthorized immigrants who had been in the country since the early 1980s. The measure was favored four to one among Latinos in California and opposed five to four by Anglos and five to three among blacks. (In 1986, under President Reagan, a form of amnesty was approved as part of a sweeping immigration reform law.)

Demise of the Chicano Movement

The final series article traced the vigorous beginning in 1968 of the Chicano Movement and its demise around 1972. Marita Hernandez, who wrote the piece, offered this recollection:

“Through a cacophony of voices recalling the exuberance and fury of the Chicano Movement, I hoped to convey the explosive period’s frustration and its rebuke of a system that counted Mexican Americans among its least deserving citizens.

“The long-suppressed indignities erupted in open rebellion, raised voices and mass demonstrations. Though short-lived, the movement succeeded in opening eyes to the unjust neglect of Mexican American communities and inspiring a generation to never forget.

“To set the stage for the story, I chose the image of calaveras bailando [dancing skulls] to represent the movement’s vibrant spirit, now tinged with nostalgia, still being celebrated years later at a reunion of the leaders of the bygone era. The image came to me from an acquaintance who had participated in the movement herself. It seemed to represent the bittersweet memories of the story’s protagonists as recounted in the text.”