Security 360°

MAPPING MILITARIZATION IN AMBOS NOGALES

Presented by The University of Arizona School of Journalism

Security along the U.S.-Mexico border is a multibillion-dollar industry. It drives political agendas. It damages the environment. It also has direct impacts on the people who live along the almost two-thousand-mile frontera between Mexico and the United States. Produced by University of Arizona journalism students, this reporting project hones in on one specific community of the borderlands, Ambos Nogales. What began as a simple endeavor to visualize security in one-square mile of Ambos Nogales, ended up expanding to quite literally a 360° view of the issue. From the history of militarization and the voices and responses to security, to the social and economic costs to the future of security in the region, this multimedia effort aims to improve public understanding about militarization and what it means to the people who live on both sides of this small stretch of the Arizona-Sonora line.

The Mapa

Security spotting in Ambos NogalesBy Amanda Burkey, Hana Pape & Kristina Savage

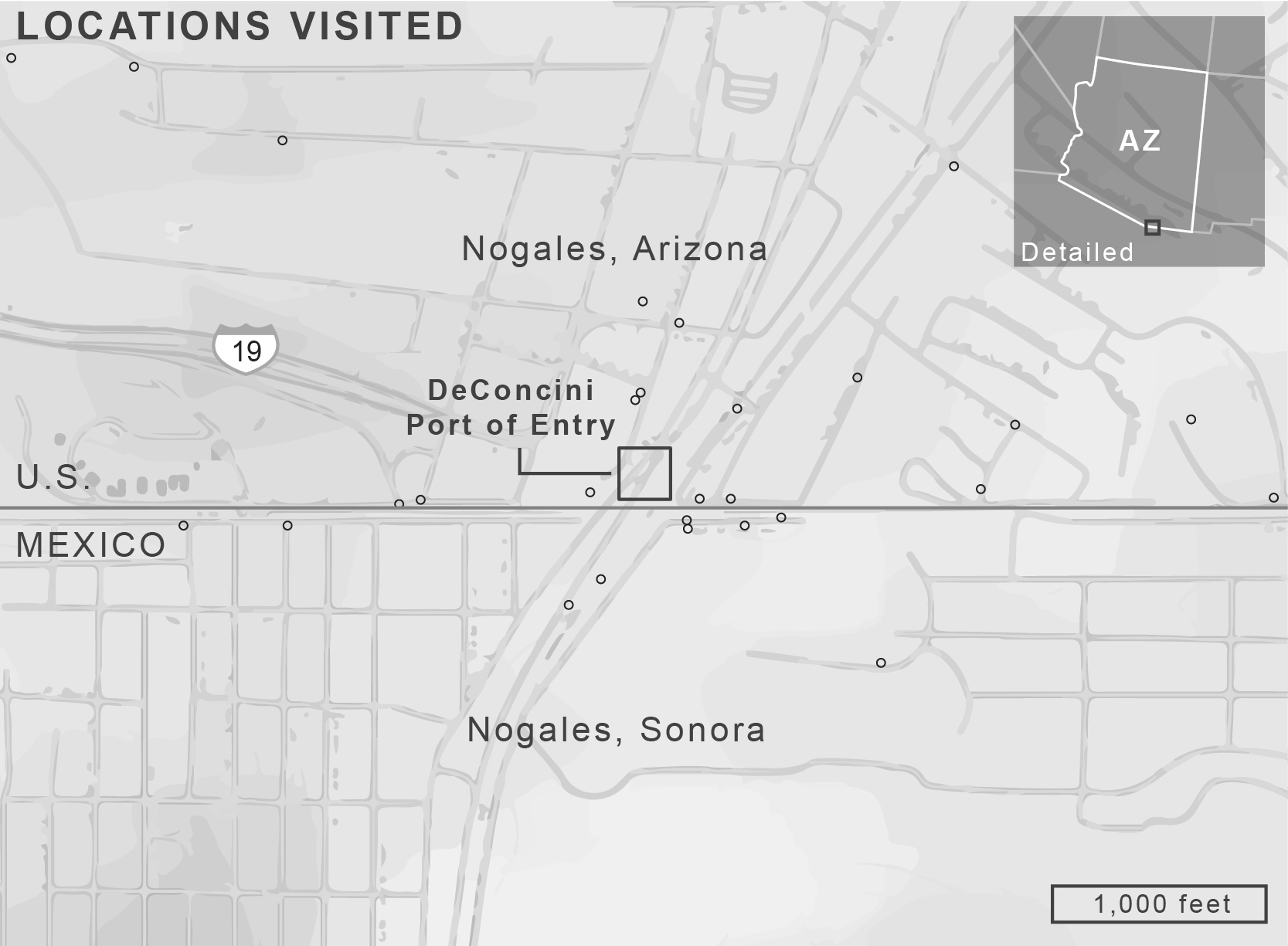

In Ambos Nogales, border security is part of everyday life. Walls, checkpoints, floodlights, and border patrol agents are ubiquitous on both sides of the border. This mapa highlights the tools of border security present in just one square mile of Ambos Nogales, extending half a mile north, south, east and west of the DeConcini port of entry on the U.S.-Mexico border.

Security Costs

It’s expensiveBy Alex Devoid, Hana Pape, Taylor Nye & Alicia Vega

Border security is expensive. The U.S. government spent an estimated $18 billion on immigration enforcement, according to a 2015 Department of Homeland Security Budget-in-Brief. The annual budget for the U.S. Border Patrol alone has increased from only around $250 million in 1990 to over $3.5 billion in 2014, according to the U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

While U.S. citizens pay for security with their tax dollars, undocumented migrants pay with their lives. The Border Patrol’s “prevention through deterrence,” policies drive migrants to the most inhospitable parts of the borderlands. As a result, the journeys that migrants take have become more dangerous, leading to an increase in the number of migrant deaths. Between 1998 and 2013, 6,029 deceased migrants were found on the U.S. side of the border, according to the International Organization for Human Migration.

In addition to lost lives, migrants are subjected to the physical cost of an arduous trek, along with psychological and emotional costs of a possibly violent apprehension or detainment at the hands of Border Patrol, as stated in a 2013 University of Arizona Latin American Studies Immigration Report titled “In the Shadow of the Wall: Family Separation, Immigration Enforcement and Security Preliminary Data from the Migrant Border Crossing Study.” The economic and social costs of militarization along the Nogales, Arizona/Sonora border also affects the lives of those who live on in this crossborder community, and whose daily lives are touched by both the tax dollars spent on fortifying the border as well as the legislative policies that spring from these expenditures.

Killed by Border Patrol agent

Jorge Solis-Palma, 28, Mexican

Killed in Douglas, Ariz., 2010

Ramses Barron Torres, 17, Mexican

Killed in Nogales, Sonora, 2011

Carlos Lamadrid, 19, U.S.

Killed in Douglas, Ariz., 2011

Byron Sosa Orellana, 28, Guatemalan

Killed near Sells, Ariz., 2011

Jose Antonio Elena Rodriguez, 16, Mexican

Killed in Nogales, Sonora, 2012

Margarito Lopez Morelos, 19, Guatemalan

Killed in Baboquivari Mountains, Ariz., 2012

Gabriel Sanchez Velazquez, late 20’s, Mexican

Killed near Apache and Portal, Ariz., 2014

Jose Luis Arambula, 31, unknown

Killed in Green Valley, Ariz., 2014

Amaro Lopez, 23, Mexican

Killed near Tucson, Ariz., 2014

Economic costs

Referred to as Ambos Nogales, the twin communities of Nogales, Ariz. and Nogales, Sonora are two cities whose histories are inextricably tied, especially underscored by the economics of the wall.

Nogales, Sonora, has a population of about ten times that of Nogales, AZ, according to their 2010 and 2013 censuses, respectively. Since about 1910, economic trade has been a major part of the economy of both cities, according to the Pimeria Alta Historical Society, but increasing border security made it more difficult than ever for employees and goods to cross, according to a publication by the Border Research Partnership entitled, “The State of the Border Report.”

As one of the effects of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), Nogales, Sonora, experienced population growth of about 50 percent since 1990, and manufacturing accounts for over 60 percent of the city’s gross domestic product, according to a report on border economy from the University of Arizona Eller School of Business Management titled “Maquiladora Related Economy of Nogales and Santa Cruz County.” Nogales, Arizona depends heavily on commerce coming from the Mexican side of the border, a large part of the city’s income stems from the people who cross every day to engage in commerce.

Families affected

According to the ACLU’s Humanitarian Crisis: Migrant Deaths at the U.S.-Mexico Border report, the Mexican Consulate offices in the U.S. answer hundreds of inquiries about missing relatives every years. They sift through any documents that could provide leads to their family members’ whereabouts. The Pima County medical examiner estimated that 75 percent of migrant remains are identified, which is low when contrasted with the 99.5 identification rate of U.S. citizen remains.

Additionally, 51 percent of those who cross the border have at least one family member who is a U.S. citizen, and almost one out of three in a survey said that their current home is in the United States, according to a report by the University of Arizona’s Center for Latin American Studies titled, “In the Shadow of the Wall: Family Separation, Immigration, Enforcement and Security.”

View our 360° video

(Chrome browser is recommended.)

Frontera Formations

A century of build upBy Kendal Blust, Amanda Burkey, Kristina Savage & Barbara Teso

Security on the U.S.-Mexico border has not always looked as it does today. For much of our history as neighbors, the people in Ambos Nogales have co-existed on the border, or frontera, with minimal physical divisions. After Congress ratified the Gadsden Purchase in 1854, which split the land into two nations, a series of stone and cement pillars were erected to demarcate the boundary between both Nogales.

“

Since the 1990s, there has been a dramatic upswing in border militarization in both boots-on-the-ground and on infrastructure.

according to historical data

The presence of human and physical barriers between the two countries has increased steadily since the 1920s, shaping the contemporary border. Since the 1990s, there has been a dramatic upswing in border militarization in both boots-on-the-ground and on infrastructure. The imposing 20-foot divide that separates Nogales, Arizona from Nogales, Sonora is one of the most recent pieces of militarization that has been made possible through and funded by U.S. immigration legislation.

In a post-9/11 era there are continued calls for more security. The obtrusive metal structure dominates the landscape. Supporters of the wall say it serves a purpose and deters undocumented migration north into the U.S. Opponents see the wall as unwelcoming sign to our neighbors, and say it deters positive interactions among those living in this cross-national community.

1920s, Beginnings of Buildup

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 and the Gadsden Purchase in 1854, defined the current border between the United States and Mexico. Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1924 in an effort to reduce immigration, and placed annual quotas on the number immigrants from Europe. This legislation also established the U.S. Border Patrol. A moratorium on immigrants from China began in 1882 through the Chinese Exclusion.

1950s, Mass Deportations

The border between Nogales, Ariz., and Nogales, Sonora, began to look much more defined as infrastructure increased. At the same time, in 1954, the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service launched “Operation Wetback,” giving Border Patrol agents the authority to launch a mass deportation effort. The INS reported that more than one-million undocumented Mexicans were detained and deported that year. Like other mass deportation efforts, “Operation Wetback” occurred during an economic downturn.

1990s, More Agents and Infrastructure

In 1994, the Tucson Sector of the U.S. Border Patrol announced the implementation of “Operation Safeguard.” The policy resulted in a significant increase in the number of border patrol agents, construction of new fences and the addition of high-intensity lighting near the City of Nogales. The operation forced migrants into open desert areas and contributed to a dramatic increase in migrant deaths. (Jeffrey D. Scott)

Early 20th century to today

The changes along the border between Nogales, Arizona and Nogales, Sonora are clear in this before and after short at the historical Main Street Port of Entry. Now called the Morley Gate, the port of entry was built in the 1920s and renovated in 2011. Before the renovation, the gate was only able to process two people at a time. (Historical photos: Courtesy of the University of Arizona Special Collections; Modern photo: Amanda Burkey)

Teresa Leal, The Changing Border

As a historian and longtime resident of Ambos Nogales, Teresa has seen the many changes in border security and its effects on this community.

By Kendal Blust, Carolina Espinoza, Alejandra Fisher & Lia Vázquez

Migration, borders and security are at the center of pressing worldwide controversy. The protection of borders and borderlands is touted as essential to the wellbeing of nations and their citizens. Much of the technology used on borders is justified as a means to protect citizens from harm, including drugs, human trafficking and terrorism. Yet, this assumption is being brought into question as growing numbers of people are emigrating from countries rife with violence, war and poverty.

Ambos Nogales faces many of the same questions and challenges. “Voices” is a collection of responses to security on the U.S.-Mexico border in Ambos Nogales from those who perhaps know it best: the residents on both sides. Among the people of Ambos Nogales, there are differences of opinion.

From the economy and safety to public health and discrimination, each person’s experience on the border is different. Yet, as borders, migration and security continue to be hotly contested issues in the United States and around the world, the insights and experiences of the people directly impacted by the physical and political changes on the borderlands are often left out of national and supranational debates.

German Peña, Nogales, Arizona

Luis Vásquez, Nogales, Sonora

Erasing the border

Artist Ana Teresa Fernández has responded to militarization using her tools of resistance, paint and a paint brush, to “erase the border” all along the U.S.-Mexico border. On October 13, 2015, she landed in Ambos Nogales with pale blue paint. Members of the community joined in to cover the wall in blue in an effort to make it blend in with the sky, at least on the Sonoran side. The U.S. government doesn’t allow people to put anything on the American side of the wall.

“

All I use is my imagination and paint… to dream of a space that would allow us to coexist side by side without hate, without violence, without oppression.

Ana Teresa Fernández, Artist

Fernández’s work has gained national attention as part of a larger movement of art and activism along both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border that is re-imagining what the border looks like and symbolizes for people along either side.

“I don’t use text. I don’t use slogans. All I use is my imagination and paint,” Fernández says. “I used these two things to dream of a space that would allow us to coexist side by side without hate, without violence, without oppression.”

Thick, rusty-brown steel plates loom 20-feet high over Ambos Nogales, signaling the physical and symbolic delineation between the United States and Mexico.

Credits

Reporters

Sophie S. Alves, Kendal Blust, Amanda Burkey, Justin Campbell, Mónica Contreras, Alex Devoid, Carolina Espinoza, Alejandra Fisher, Ana Ilie, James Myers, Taylor Nye, Hana Pape, Kristina Savage, Barbara Teso, Lia Vásquez, Alicia Vega, Madison Yuill

Project Designer

Kedi Xia

Project Adviser

Dr. Celeste González de Bustamante

Acknowledgements

The Security 360° Reporting Team would like to thank the following people and organizations for their support on the project.

César Barron, Radio XENY

Miriam Davidson

Veronica Reyes-Escudero, UA Special Collections

Jennifer Hijazi, UA Journalism Graduate Student

Mike McKisson, UA School of Journalism

Nogales Community Development

Santos Yescas

Nils Urman

The people of Ambos Nogales

Pimería Alta Historical Society

University of Arizona Office of Student Engagement

University of Arizona Santa Cruz, Nogales, Arizona